Don't Create Solutions, Solve Problems

December 14, 2022

I have been a professional software creator for over 25 years.

In this time, I have seen and used numerous methodologies spanning the spectrum, from completely informal and ad-hoc to agile (and various interpretations of Scrum and Kanban) to traditional waterfall.

I have also seen and used more requirement and solution specification templates and gating approaches than I can remember, varying from completely informal and ad-hoc to those based on rigorous system requirements, architecture, and design specification documents and multi-stage review and sign-off procedures.

For a majority of my career, the titles I've held typically included something along the lines of "creating solutions to help development teams deliver features".

My perspective on this has changed quite a bit and, in retrospect, I think this description misses the mark in a significant way.

Your most valued skill as a software creator is not the programming languages you've mastered. It isn't your knowledge and skills in a particular programming paradigm, technology platform, set of frameworks and libraries, or even a set of design patterns and software development practices you've acquired experience in using.

These are tools—valuable tools, without question—but they are a means to an end, and that end is solving a problem.

As a software creator, the most valuable skill I offer is the ability to solve problems.

A solution, whether it is delivered in the form of a design document or a software system, has no value to my clients and employers if it fails to solve a problem.

I have a bookshelf, right now over my shoulder where I'm writing this, that is full of books on theoretical and practical knowledge on subjects spanning music, art, business, coaching, computer science and software development. I have plenty more, in physical and electronic form, in bookshelves, drawers and boxes throughout my home. Many of these are prized possessions that I've read many times and refer back to frequently to recall details and tease out new insights.

Not a single one of them is titled "How to Solve a Problem".

It seems to be such an obvious topic that, perhaps in my hubris, I haven't considered the need nor have been asking myself the right questions.

Perhaps the answer lies within many of these books and I just need to read between the lines, or zoom out to recognise some common outlines and patterns.

The latter is the closest to the truth, in my experience, and I'm going to show you the method I've extracted and rely on most often to ensure the solutions I create are valued because they solve a problem.

The Scientific Method

Let me start with a familiar analogy.

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterised the development of science since at least the 17th century. If you recall your high school science classes, the method can be summarised as iterations of some variation of the following steps:

- Make Observations

- Ask a Question

- Do background Research

- Construct a Hypothesis

- Test with an Experiment

- Analyse data to Test Predictions

- Draw Conclusions

The scientific method is not only a reusable process in which each step serves a specific purpose, but one in which each step is founded on general principles worthy, as noted by scientist and philosopher William Whewell, of "invention, sagacity, [and] genius".

To put it another way, one could write a book on the set of principles, and how to apply them, for each step of the scientific method.

As for the subject of my analogy, it is based on the observation that the scientific method is a design pattern for solving the problem of acquiring knowledge (forming a theory based on a hypotheses) for a given context (a question based on observation). I'll come back to this point further on.

One of the most well-known and highly influential books in the software development profession is Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, by Gamma Eric, Helm Richard, Johnson Ralph, and Vlissides John. It is also commonly referred to as the Gang of Four book, in reference to the four authors.

This book is a catalogue of well-known creational, structural, and behavioural object-oriented design patterns.

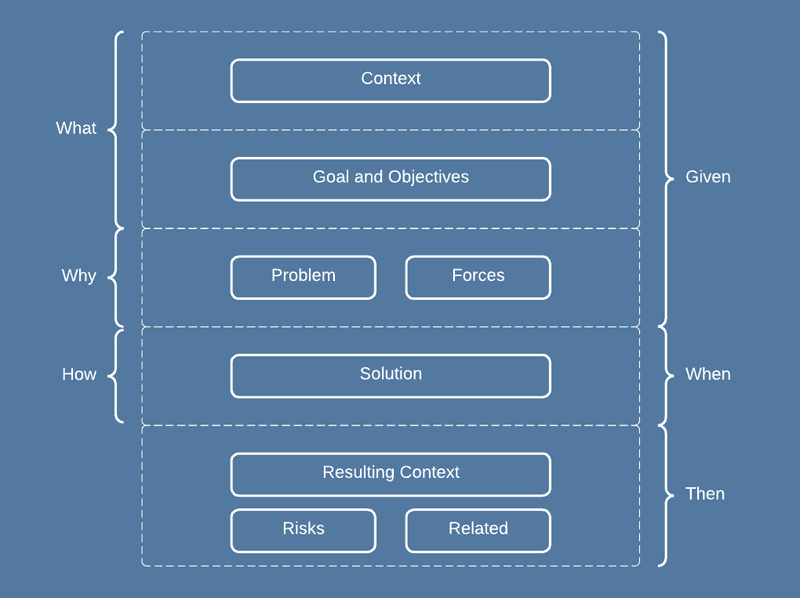

What I want to call attention to, however, is the method this book helped establish—the template and meta-model—to describe a design pattern, as this distils what I refer to as the Design Pattern Method of solving a problem.

The Design Pattern Method

Here are the generalised steps:

- State the applicable Context

- Identify the Goal and Objectives

- Identify the Problem and Forces

- Describe the Solution

- Describe the Resulting Context

- List potential and/or observed Risks and Mitigation

- List Alternative and Related Solution Patterns and Practices

Let's break down each of these steps.

State the Context

A solution is rarely a one-size fits all thing. The context indicates the circumstances when a particular solution is applicable.

State the Goal and Objectives

The next step to solving a problem is a clear understanding of the goal and objectives of the individual or group seeking a solution. The more you understand about the expectations behind a solution request (the what and why), the better you will be able to empathise with the requester and appreciate the problem that will influence the decisions you will make in converging towards a solution.

This is the first checkpoint and opportunity for review and feedback from the requester. You want to be sure you share an understanding of the expected outcome.

Identify the Problems and Forces

This is where you list and elaborate all of the pain points and obstacles the requester is experiencing, and where you really dig in and explore the problem space and what is motivating them (the why) to seek a solution. This will lend clarity to the context and objectives.

This is also where you list and elaborate the forces—the constraints, standards, conventions, best practices, and any other significant considerations—that will influence you solution decisions. These forces may be a combination of inputs from the requester as well as your own research, knowledge and experience. They help converge solution space options to what is most applicable and appropriate to the problem at hand.

This is the second checkpoint and opportunity for review and feedback. You want to be sure you share an understanding of the problems (and their relative importance) before spending too much effort on a solution. It is also your first opportunity to share expectations on the solution space guardrails you intend to leverage for your solution.

Describe the Solution

The solution is how you solve the problem. This is where you apply your expertise to model a solution that

- Meets the objectives

- Addresses the problem

- Complies with the forces

- Considers the context

Consider this a solution checklist. The more clearly you are able to trace your solution decisions back to these checklist items, the more clearly you will be able to understand and communicate the solution, and rationalise it and defend it, if necessary. It will be much easier to sway opinions in your favour when you've laid out your solution in a manner that clearly explains how it addresses each of the requester's concerns.

You may include more than one solution option under consideration here, but the goal is to converge to a single recommendation. As your third checkpoint, perhaps you need feedback and further elaboration on the problem space considerations to help converge the solution decision to the appropriate recommendation.

Describe the Resulting Context

This is where you describe the expected results of applying the solution and highlight how it solves the problem and achieves the goal and objectives in a manner that acknowledges the forces.

By doing so, you are providing explicit traceability of the solution to the problem space.

Identify Risks and Mitigation

This is where you highlight any limitations to your solution and risks in applying it, especially any problem space considerations that could not be met.

A solution may not be able to fully address all concerns and will typically trade off one consideration for another. Ideally, these trade offs would be informed by the priorities of the stated problem and forces.

You can list any potential mitigation measures to each issue, and you are free to elaborate on them as necessary. If they are speculative, you could reserve elaboration until necessary, perhaps iterating on the solution with new insights and additions to the context and objectives, or problems and forces. Alternatively, you could address them as part of entirely separate solution, as part of a more specific use case.

Reference Related Practices and Patterns

This is where you can reference any solution practices and patterns that may be related, but not necessarily appropriate to the recommended solution. This may include solution options that were initially considered but ultimately discarded in favour of the recommended solution.

This helps flesh out your own solution decision process, and may serve as valuable information for future reference should anyone need to revisit the solution decisions.

The Payoff

For the icing on the cake, let me circle back to my analogy to the scientific method as an example of a design pattern.

You may now appreciate that the method and template (i.e., the meta-model) for defining a design pattern is, in itself, an example of a design pattern.

To put it another way, the design pattern method is a set of steps and principles for solving a problem in a reusable manner.

Case in point, here is a definition of the design pattern method using the design pattern method:

Context

As a professional software creator, you deliver software that provides value to your clients and employers.

Goal and Objectives

The goal is to deliver software that solves client and employer problems.

An objective is to design and deliver solutions as input to the software delivery cycle.

Problem

The software solution must solve client and employer problems.

Forces

- Software solutions that are reusable are more valuable than bespoke solutions.

- Reviewing proposed software solutions with stakeholders, in order to confirm expectations have been understood and will be met, is a best practice to improve the quality of delivered software.

Solution

Use the Design Pattern Method to define the solution.

Resulting Context

The resulting solution includes the solution description within the Design Pattern Method framework.

As a result, the solution describes not only how the problem is solved, but what problem the solution solves, why the solution is appropriate, and when the solution is applicable to the problem.

The resulting context also describes how the problem is solved by explicitly describing the expectations of applying the solution and how they address the problem, objectives, and goal—effectively demonstrating traceability of the solution to the problem.

Risks and Mitigation

Every solution involves decisions between options and trade offs, based on assumptions and uncertainty.

Stating the risks, if assumptions do not hold, raises awareness of potential undesired outcomes. Mitigation measures anticipate and reduce the impact if such outcomes result.

Related Practices and Patterns

Alternative solution practice and pattern options informs the audience of other options that were considered, but deemed less appropriate.

References to related practices and patterns provide additional information...

- for consideration for different circumstances

- for a deeper dive for implementation

To Wrap Things Up

This article defines a method and framework to help bridge the communication gap between the problem space and solution space stakeholders.

It also fosters a practice and discipline for taking a top-down approach to solution development, by focusing on solving a problem instead of forcing a problem to fit a solution.

A problem-solving approach fosters empathy and develops domain knowledge through the perspective of the problem space.

Technology is ephemeral and constantly subject to evolution, deprecation, and obsolescence. Insight and knowledge of the problem domain is a more durable asset that transcends technology decisions.

Lastly, this method documents not only the solution (the how), but the reasoning (the what, when, and why) behind the solution design decisions. This is critical information for subsequent changes, which otherwise may be based on incorrect assumptions, or may require re-discovery of the problem and solution space considerations.

— Cory Serratore